Sanitizing, Escaping, and Encoding

“We need to sanitize this data” is a phrase I have heard too many times in the context of web security. It always makes me a little nervous.

The implication of the term “sanitize” is somehow cleaning the data or rendering it “safe”. But the details of how that safety is achieved are a little vague.

Often it means simply searching for a function containing sanitize and blindly using that function.

That is usually the wrong thing!

Injection Vulnerabilities

Injection vulnerabilities, including cross-site scripting, are a top category of web vulnerabilities.

The root cause of injection vulnerabilities is the mixing of code and data which is then handed to a parser (the browser, database driver, shell, etc). Injection is possible when the data is treated as code.

(See my talk about injection for a deeper dive!)

Since proper escaping or sanitization is the mitigation for injection vulnerabilities, it is important to have a clear understanding of what those terms mean.

Escaping

The term “escaping” originates from situations where text is being interpreted in some mode and we want to “escape” from that mode into a different mode.

For example, there are ANSI “escape codes” to tell your terminal to switch from a text mode to interpreting a sequence of control characters.

The more common situation is when a developer needs to tell a parser to not interpret a value as code. For example, when one is writing a string and wants to include a double-quote inside the string:

"blah\"blah"

The backslash \ is an escape character that tells the parser to treat the following character as just a value,

not the end of the string literal.

However, especially in web security, when we say “escaping” we typically mean “encoding”:

Encoding

Encoding involves replacing special characters with a different representation.

HTML encoding uses HTML entities.

For example, < would normally be interpreted as the start of an HTML tag.

To display a < character without it being interpreted as a tag, use <.

In HTML, & is the escape character. So now you can see how encoding and escaping are intertwined.

In URLs, encoding involves replacing characters with % followed by a hexadecimal number that corresponds

to the ASCII code for that character.

For example, / in a URL would normally be interpreted as a path separator.

To pass in / without it being interpreted that way, use %2F.

This is called “URL encoding” or “percent encoding” and the % character is the escape character.

The value after % is the hex representation of the ASCII code for the desired display character.

Encoding special characters is typically a very simple and straightforward process. Characters are simply replaced with their encoded value in a linear fashion.

The encoding scheme used depends on context. For any type of interpretation (HTML, JavaScript, URLs, CSS, SQL, JSON, …) there will be a different encoding scheme. It is important to use the correct encoding for the context.

Also note that encoding is a completely reversible process! Given an encoded string, we can easily decode it back to the original value.

Sanitizing

Unlike encoding and escaping, sanitization involves removing characters entirely in order to make the value “safe”.

This is a complicated, error-prone process.

Here is a classic example of bad sanitization:

# Remove script tags!

def sanitize_js(input)

input.gsub(/<\/?script>/, "")

end

sanitize_js("<script>alert(1)</script>") # => "alert(1)"

sanitize_js("<scri<script>pt>alert(1)</scr</script>ipt>") # => "<script>alert(1)</script>"

This is not just an amusing theoretical example - I have seen this exact approach used in production applications.

Since sanitization is so difficult - nearly impossible - to do correctly, most sanitization implementations have seen a number of bypasses.

Also, unlike encoding, sanitization is not reversible! Information is lost when the data is sanitized. You cannot retrieve the original input once it has gone through a sanitization process. This is rarely a desirable side-effect.

Sanitization can also mean removal or replacement of sensitive data. That is a different usage not being discussed here.

Using the Right Approach

From a security perspective, contextually encoding untrusted values at time of use is the preferred approach.

The tricky part is understanding the output context of the data and which encoding to use. HTML can easily have more than four different contexts in a single document! Also, it makes no sense to use HTML encoding in SQL.

When possible, use encoding routines provided by libraries or frameworks.

Sanitization should be reserved for cases when encoding is simply not possible. For example, if an application must accept and display HTML from users. There is no way to use encoding in that scenario.

Again, when possible, do not write your own sanitization! Use existing libraries.

Summary

When discussing handling potentially dangerous data, be precise with terms!

The security industry seems to have settled on “escaping” to actually mean “encoding”. In other words, a reversible transformation that encodes special characters so they will not be interpreted as code.

Sanitization, in this context, means an irreversible stripping of special characters.

When possible, prefer encoding/escaping to sanitization!

See Also

OWASP Cross-Site Scripting Prevention Cheatsheet

Reviving an HP 660LX in 2019

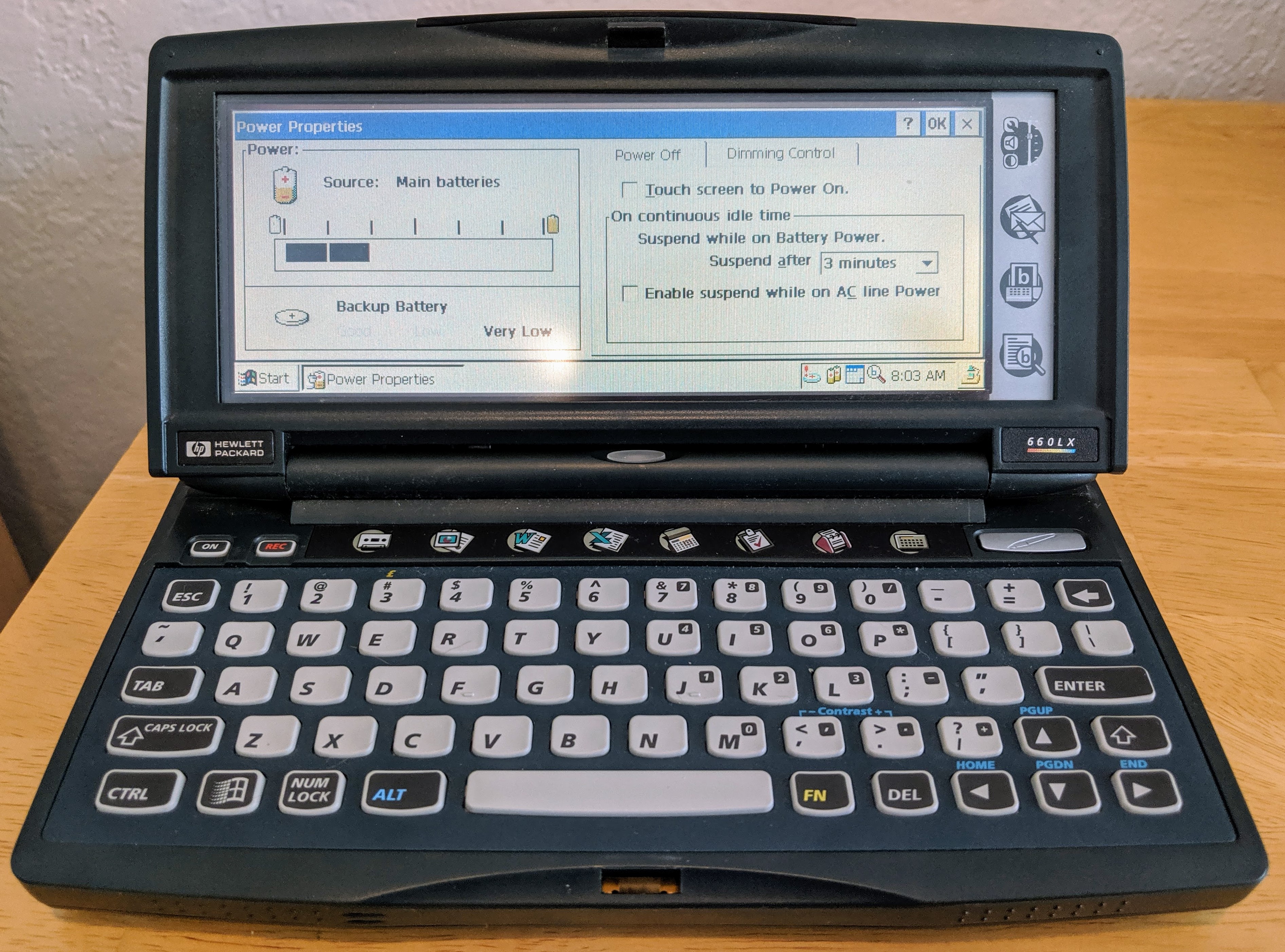

It started off as a joke…

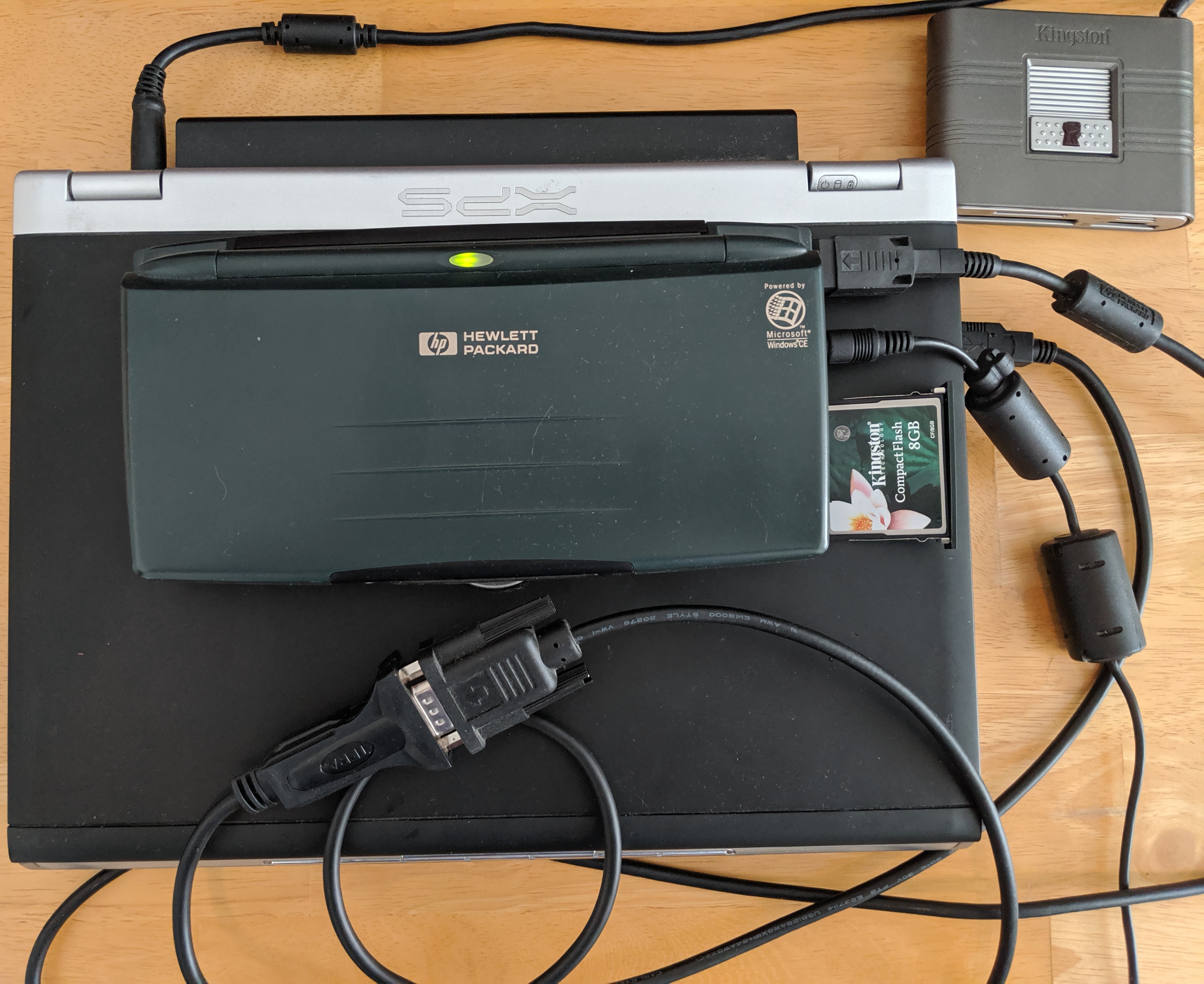

Just setting up my burner machine for @defcon pic.twitter.com/Dz9pjCBTCo

— Justin Collins (@presidentbeef) June 29, 2019

I had spent some time several years ago trying to get Linux running on this machine via the (defunct) JLime project, so I had some of the pieces available to actually get this little “pocket computer” going again - mainly compatible CompactFlash cards and an external card reader. But I was mostly joking.

Then I starting thinking how funny it would be to actually sit in a talk and take notes at DEF CON on an ancient “laptop”…

Battery Power

The reason I was mostly joking is because the batteries in the 660LX were not working at all. So, what was I going to do? Plug it into the wall? That’s just sad, not funny.

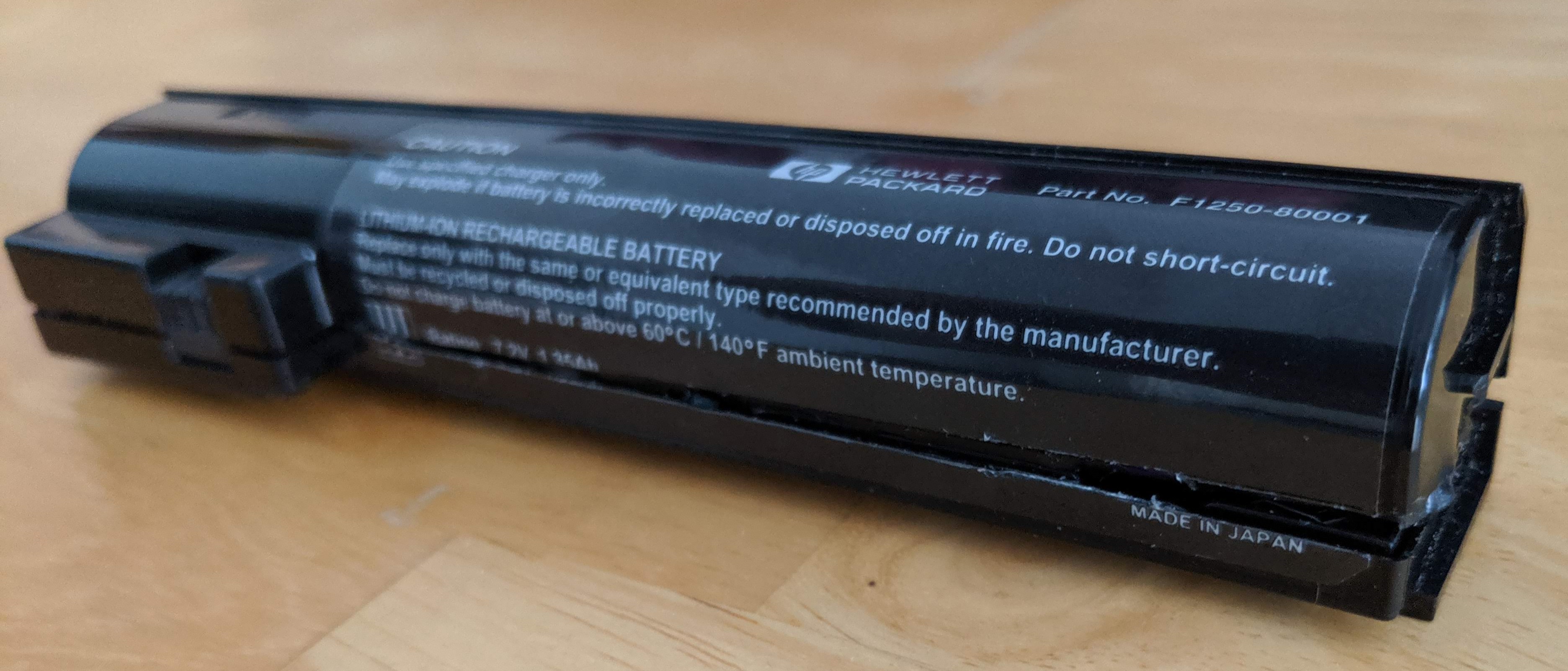

I started looking around online for replacement batteries for this machine from 1998. Despite visiting several rather shady websites, for some reason I was unable to find anyone selling twenty-year-old laptop batteries. Some sites claimed to offer a replacement, but from the pictures it was clear they would not work. The only real possibilities I found were complete sets - a 660LX, manual, cables, etc. I already had a 660LX, acquired for free, so I really didn’t want to spend $100+ on another one! Also, kind of ruins the joke to do so.

(Side note: the 660LX has a button battery for backup power. Searching for “HP 660LX battery” will return sites trying to sell you a little CR2032 battery.)

Now, I will admit my mental model of a laptop battery was a block of chemical goop inside of some plastic wrap with some wires coming out of it. After ungracefully disassembling the 660LX battery, I found inside it was just two smaller batteries?!

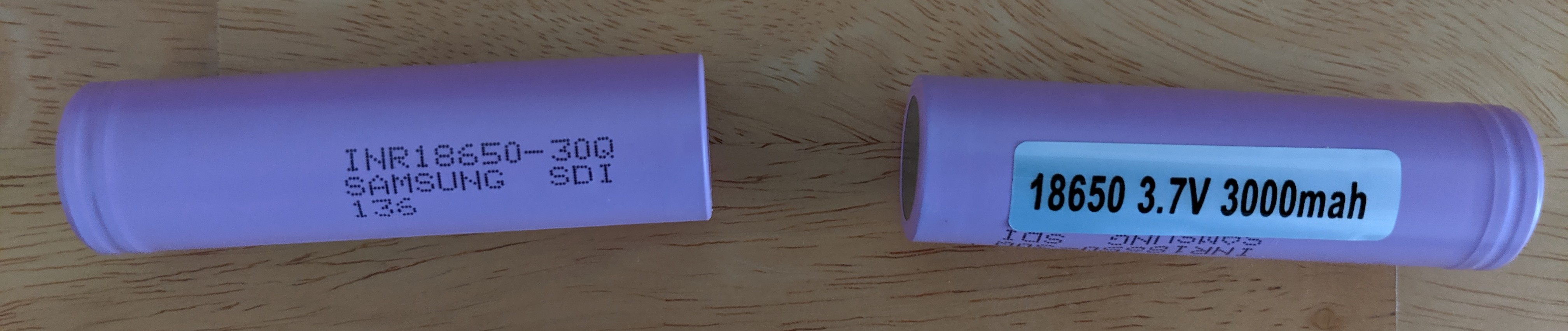

The batteries said “US18650S SONY ENERGYTEC” on them.

While I didn’t find those exact batteries, some investigation showed the 18650 battery in general is extremely common.

There are two kinds of 18650 - one with “caps” (that little nub on the top) and one without. It seems the ones with caps are safer, as they have an internal circuit to keep them from blowing up. However, as you can see above, I needed the kind without caps. Presumably the little circuit board regulates charging the batteries.

The Internet suggested sticking to “brand name” batteries, but weirdly Amazon does not carry any of those. I took a chance on a pack of batteries which reviewers suggested looked like “genuine” Samsung batteries.

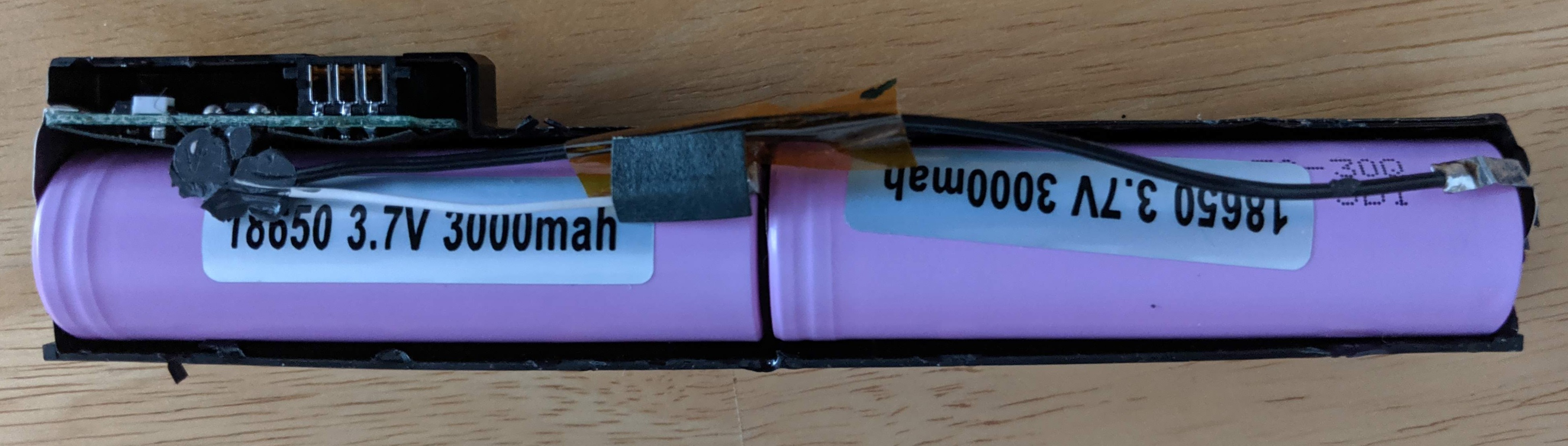

I carefully ripped the old batteries out. The leads from the batteries to the little circuit board were actually soldered to the batteries, so I pried them off with a screwdriver. Probably not a great idea unless they are really, truly dead.

With some effort, I shoved the new batteries back in the case and sandwiched the wires back in as well. I didn’t bother actually attaching/gluing/soldering anything.

I did, however, scare myself when I generated a terrifying electric arc as I tried to use a screwdriver to squeeze everything back into the battery case.

I may have damaged the case just a tiny bit when I gently pried it open, contributing to it looking slightly sketchy when I tried to close it back up.

But, who cares how it looks…does it work??

YES!

Hahahaha now I can walk around using my relic with no wires!

Software Updates

Nowadays, a device that can’t connect to anything does not seem like much fun.

Of course I wanted to hook this Windows CE 2.0 machine up to the Internet!

The HP 660LX has a “PC CARD” expansion slot where you can slap in an Ethernet or wireless card, but of course it is ancient and you have to be careful about compatibility.

Enter HPC: Factor! This is a website/forum full of useful information. For £10 you can get access to a ton of file downloads (software, drivers, updates) for a year. Totally worth it.

One thing I learned quickly is that you need the service pack for Windows CE 2.0 and the Network Service Pack in order to have a chance at getting a wireless card to work.

At this point, I had been transferring files to the 660LX via a compact flash card (which, at 8GB, probably blew the little machine’s mind). However, most software for Windows CE requires installation via ActiveSync.

What is ActiveSync? Well, originally these “pocket computers” weren’t meant to be tiny laptops. They were more like little helpers you use while you are away from your main machine, then you sync up files, calendars, email, etc. when you went back to your desk.

ActiveSync was the software used to sync between a pocket computer and your main machine.

Now, for Windows CE 2.0, the recommended version of ActiveSync is 3.8. The very newest operating system supported by ActiveSync 3.8 is Windows XP.

By pure luck, I had an old Windows XP laptop and I was able to install ActiveSync!

BUT… you need a special serial cable to hook up the 660LX. At first I poked around eBay, but no luck. Yet, in the back of my mind, I was pretty sure I still had that cable somewhere. I searched all around my office and dug through my big box of (mostly useless) cables, but still no luck.

Just when I gave up (of course) I found it!! Yay!!

BUT… turns out I don’t have a serial port on my Windows XP laptop.

I thought about trying a Windows XP virtual machine on my main Linux box, but it doesn’t have a serial port, either! None of my machines had an infrared port, either.

After first buying the wrong cable on Amazon, I got an RS-232 to USB adapter and a tiny, tiny CD with drivers. Luckily, the laptop has a CD drive, so I was able to actually install the proper drivers.

After an uncomfortable amount of configuration twiddling… they connected!!

I was then able to install Windows CE 2.0 SP1 and the CE Network Service Pack.

Networking

One of my criteria for this project was to not spend much money on a joke.

After spending some time looking around, I bought a $20 wireless adapter off of eBay. $20 was really right at the limit of my per-item budget.

In the meantime, though, I found out there was another way to access the Internet.

Turns out you can “share” the networking connection on the main machine with the 660LX over the serial cable, via ActiveSync.

The only weird bit is that you need to run a proxy server on the main machine to route the connection to the Internet.

In the modern world, that is not a problem. In the land of Windows XP, however, I was not sure I would be able to get something working. I found CCProxy, which did work, despite its awful and confusing interface.

Configured the proxy for “The Internet” on the 660LX and…

Wow! The Internet!

Sadly… or not so sadly… the world has moved to HTTPS and to stronger protocols than what lowly Pocket Explorer supports. Thus, most of the web is entirely inaccessible on the device.

As a result, when the eBay seller canceled my order for the wireless adapter, I figured “meh”. Even if you can get WiFi working (which would likely require connecting to a totally unsecured network), there’s not much of the web that one can even visit.

Yes, it would be possible to use an SSL stripper, etc., but I didn’t want to go through the hassle of setting that up on Windows XP.

Wrapping Up

This turned into more of a narrative than a how-to guide. Maybe I’ll do another write-up with the details. In the meantime, I can try to answer questions about specifics.

Finding Ruby Performance Hotspots via Allocation Stats

RubyParser is a library written by Ryan Davis for parsing Ruby code and producing an abstract syntax tree. It is used by Brakeman and several other static analysis gems.

Recently I was poking around to see if there was any low-hanging fruit for performance improvements. At first, I was interested in the generated parsers. Racc outputs some crazy arrays of state machine changes. Instead of generating arrays of integers, it outputs arrays of strings, then splits those strings into integers which it loads into the final array. I thought for sure skipping this and starting with the final array of integers would be faster, but…somehow it wasn’t.

I moved on to thinking about frozen string literals, which led me to checking String allocations.

Measuring String Allocations

I found the allocation_stats gem very useful for this.

I set up a test like this to read in a file and parse it:

require 'ruby_parser'

require 'allocation_stats'

f = File.read(ARGV[0])

rp = RubyParser.new

stats = AllocationStats.trace do

rp.parse(f, ARGV[0], 40)

end

puts stats.allocations(alias_paths: true).where(class: String).group_by(:sourcefile, :sourceline).sort_by_count.to_text

This outputs a report like this (truncated here):

sourcefile sourceline count

-------------------------------------------------- ---------- -----

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser.rb 20 70686

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1361 58154

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1362 54672

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_lexer.rb 373 19019

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_lexer.rb 770 12005

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_lexer.rex.rb 109 8252

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1015 6818

Right away, these look like some juicy targets.

Version Creation

Let’s take a look at the first one:

class Parser < Racc::Parser

include RubyParserStuff

def self.inherited x

RubyParser::VERSIONS << x

end

def self.version

Parser > self and self.name[/(?:V|Ruby)(\d+)/, 1].to_i

end

end

On line 8 you can see the Parser.version method. RubyParser is actually not just one parser, but multiple parsers for different versions of Ruby.

So there is a RubyParser class but also Ruby18Parser, Ruby19Parser, etc. and RubyParser::V18, RubyParser::V19, etc.

To figure out the version of the current class, the code above grabs the version from the class name itself.

The problem is this code is called a lot (70k+ in the example above) to make version-specific decisions during the lexing phase. This is fairly easy to fix.

In my testing, this reduced string allocations by ~25% and parse time by 5-10%. One thing I have noticed - and you may also find if you go chasing object allocations in Ruby programs - is that reducing allocations doesn’t necessarily help with peak memory use or run time. It seems the Ruby VM has gotten pretty good at allocating and garbage collecting objects efficiently.

Debug Code

Let’s take a look at the next two large number of String allocations:

sourcefile sourceline count

-------------------------------------------------- ---------- -----

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1361 58154

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1362 54672

Interesting: just two lines apart, with over 100k allocations between them.

def push val

@stack.push val

c = caller.first

c = caller[1] if c =~ /expr_result/

warn "#{name}_stack(push): #{val} at line #{c.clean_caller}" if debug

nil

end

The two lines of interest are 3 and 4 - the assignments to the local variable c, which pull information from caller.

caller is a fairly expensive method, since it needs to generate a stack trace for the current method call.

Upon a closer look, it’s clear the c variable is only used in the message on the following line, and that message is only used if the debug flag is set.

This means we can wrap all that code in a condition, like this:

def push val

@stack.push val

if debug

c = caller.first

c = caller[1] if c =~ /expr_result/

warn "#{name}_stack(push): #{val} at line #{c.clean_caller}"

end

nil

end

This change saves 38-50% on string allocations and 20-26% on parse time.

Reading Lines

Skipping down a few unavoidable string allocations, there’s this one:

sourcefile sourceline count

-------------------------------------------------- ---------- -----

<GEM:ruby_parser-3.11.0>/lib/ruby_parser_extras.rb 1015 6818

Here’s the code:

header = str.lines.first(2)

RubyParser checks the first couple lines of a file for any comments setting the encoding for the file. The trouble is that calling String#lines will split the entire string up when we only need the first two lines.

Grabbing only the first two lines ends up being pretty trivial thanks to Ruby’s standard approach of returning enumerators for enumeration methods if a block is not supplied:

header = str.each_line.first(2)

String#each_line will lazily return the lines from the string, so it only does the work needed.

Sadly, this didn’t do much for overall string allocations and parse time since this method is only called once, but I think it’s a clear improvement to only grab the two lines needed.

Freezing Strings

Finally, back to the original idea. By the time I made it back to freezing string literals, I was feeling pretty lazy, so I just threw the frozen string header on ruby_lexer.rb:

# frozen_string_literal: true

Running the tests showed only one method where frozen string literals did not work, so these strings needed to be duped.

String allocations were reduced by 24-30%, but with almost no parse time change. Probably because these were tiny, tiny strings.

Final Metrics

With these four changes, string allocations were reduced by 75-83% and parse time was reduced by 30-37%. The test suite for RubyParser ran 33% faster on my machine.

I did not see a huge decrease in peak memory use. Maybe 3%. My guess is this is because the String representation in Ruby is fairly well-optimized already (e.g. copy-on-write).

For Brakeman, parsing is a decent part of the run time (30-60% even), so a faster RubyParser definitely makes Brakeman scans faster. From a few test scans, I saw as much as a 30% improvement in total scan time.

Final Changes

The final version of the changes applied by Ryan are in this commit.

I expect these improvements will be in the next RubyParser and Brakeman releases.